Three women at the forefront of quantum science within the PEPR Quantum

2026 International Day of Women and Girls in Science

As part of the 2026 International Day of Women and Girls in Science, the PEPR Quantum highlights three women contributing to scientific research within the program. A lecturer-researcher, an engineer, and a PhD student share their backgrounds, their work, and their missions within the PEPR and beyond.

The feature also opens a broader conversation on women’s place in research, the importance of role models, and how to inspire younger generations to engage with quantum science and engineering.

A variety of professions, missions and responsibilities

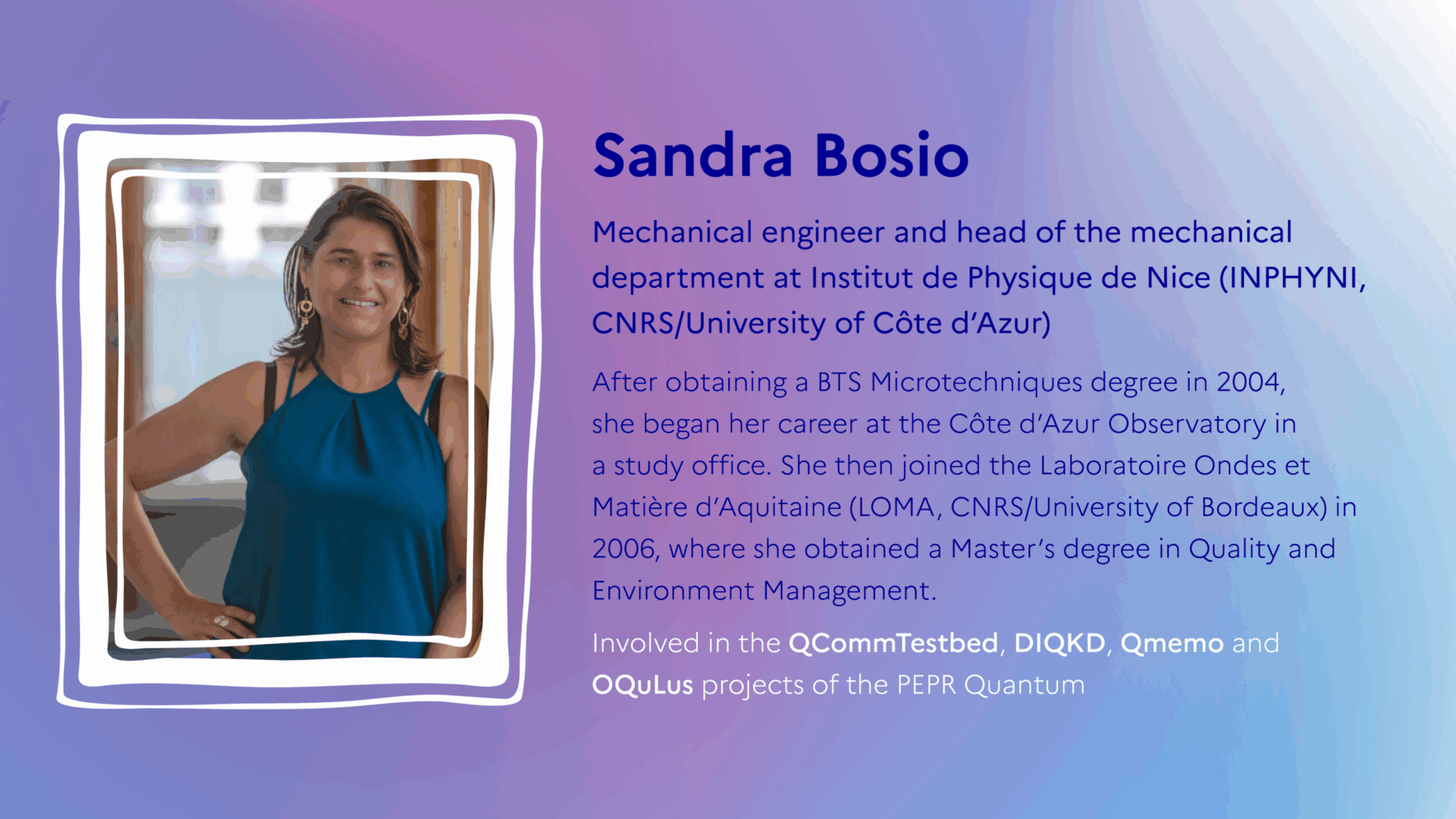

Sandra Bosio

Sandra Bosio is a CNRS mechanical design engineer and head of the mechanical department at the Nice Institute of Physics (INPHYNI). Her role is to bridge the gap between scientific intent and its mechanical implementation, by providing technical support for research. She and her team work closely with researchers to translate what is often highly theoretical research needs into reliable and innovative technical solutions, prototypes and experimental devices. She collaborates in particular with the Photonics and Quantum Information team, which works on topics such as quantum cryptography and metrology. Within this framework, she has participated in the design and production of several parts and prototypes, such as a quantum memory cryostat for storing quantum information.

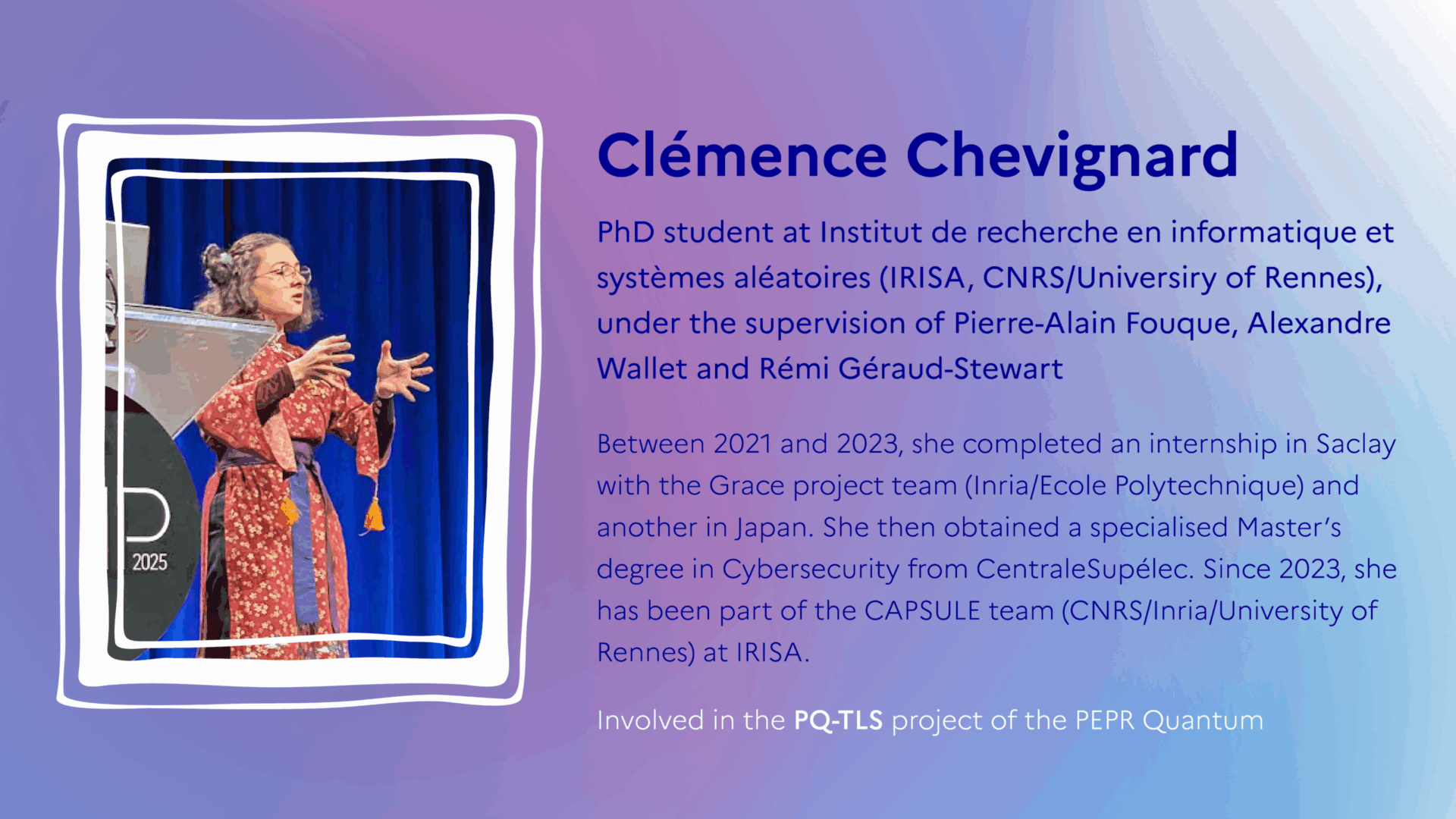

Clémence Chevignard

Clémence Chevignard is a PhD candidate at the Institute for Research in Computer Science and Random Systems (IRISA), supervised by Pierre-Alain Fouque, coordinator of the PEPR Quantum project PQ-TLS, alongside Alexandre Wallet and Rémi Géraud-Stewart. Her research focuses on the cryptanalysis of post-quantum cryptosystems.

As part of her doctoral work, she studies memory-efficient implementations of quantum algorithms. In practical terms, this involves closely examining existing quantum algorithms and refining specific steps and parameters to improve their performance. With her colleagues1, she has applied this approach to Shor’s algorithm, widely regarded as a cornerstone of quantum cryptanalysis. She also conducts classical cryptanalysis, using conventional computers to attempt to break existing cryptosystems.

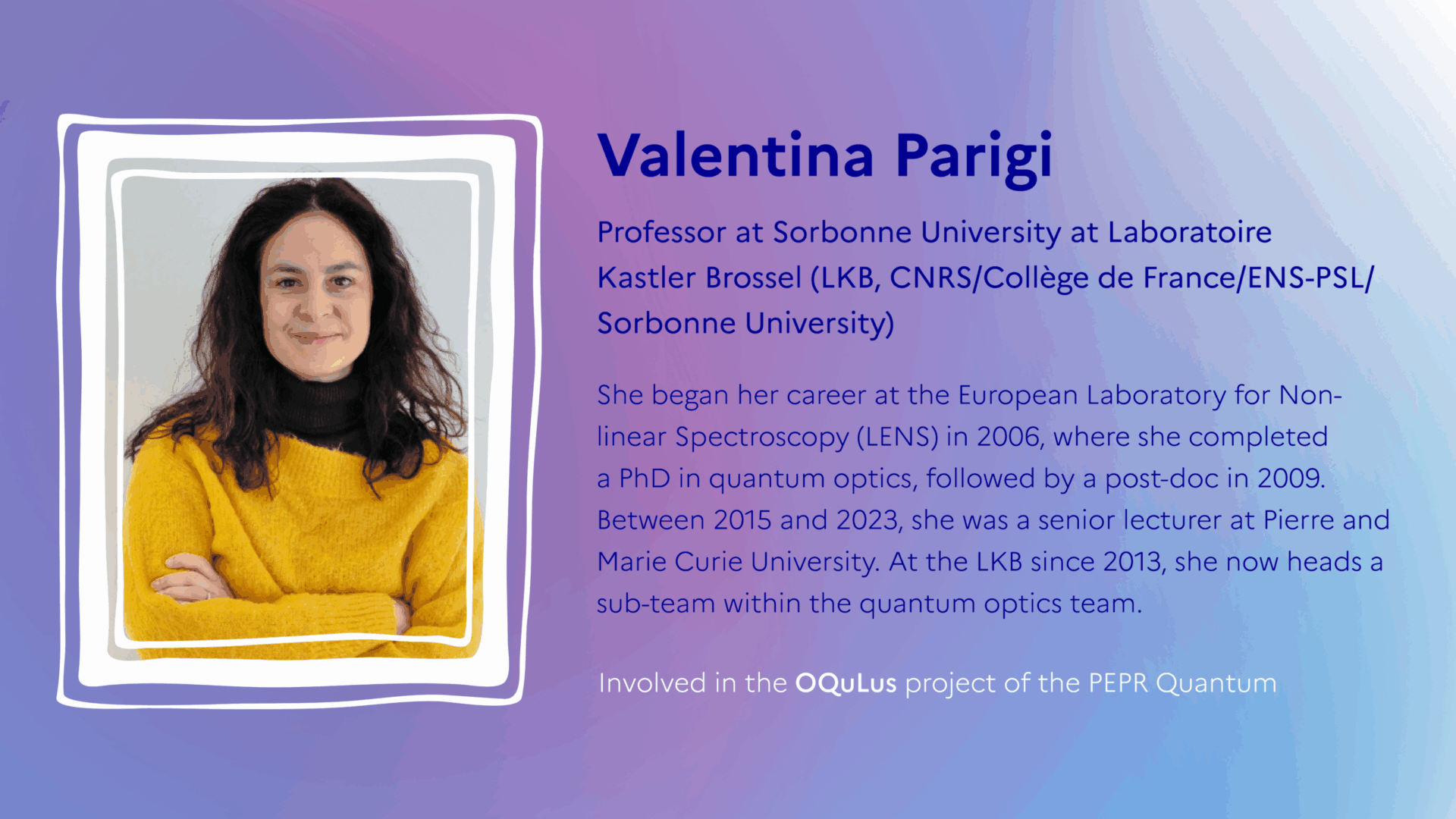

Valentina Parigi

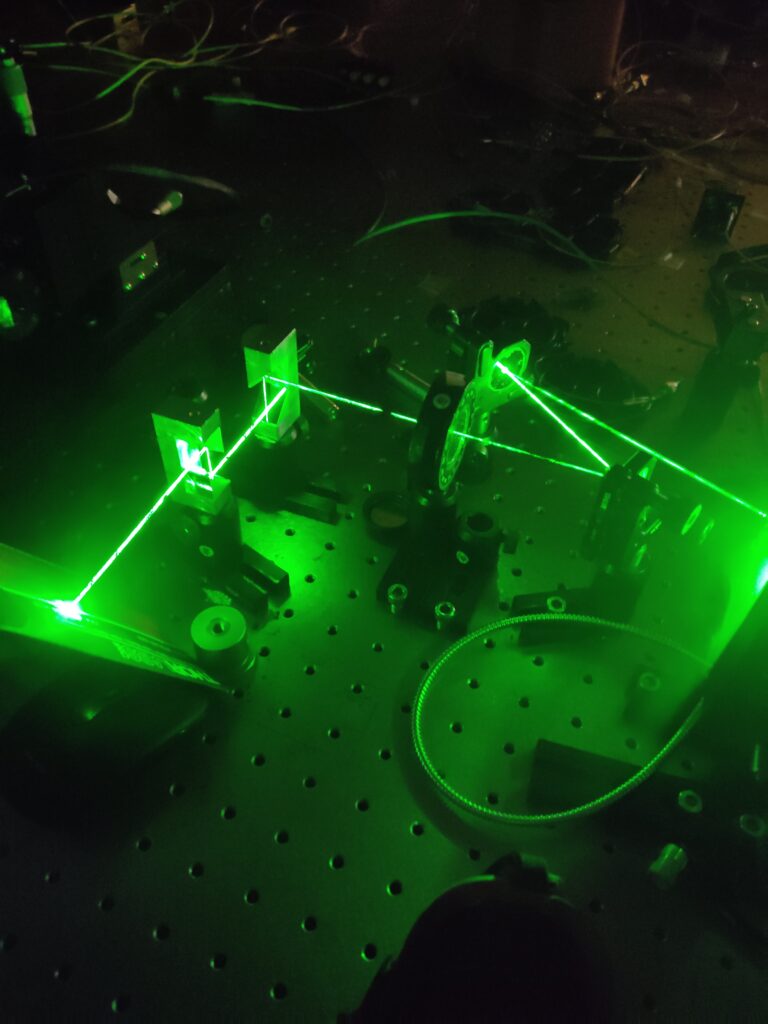

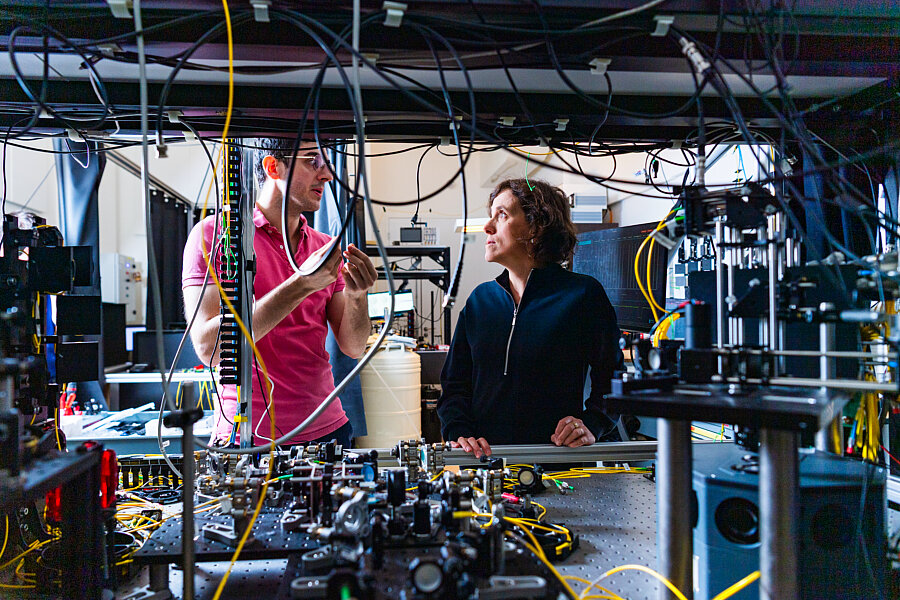

Valentina Parigi is a professor at Sorbonne University and works at the Kastler Brossel Laboratory (LKB). She is part of the PEPR OQuLus project, which aims to develop two different prototypes of photonic quantum computers—one based on discrete variables and the other on continuous variables. Her applied research focuses on the latter.

At LKB, she leads a subteam within the quantum optics group, conducting experiments designed to generate continuous-variable quantum states using femtosecond lasers, nonlinear crystals, and waveguides. These quantum systems enable encoding of quantum information through field phase amplitude.

Working in a predominantly male sector

A lack of infrastructure for women

The three women interviewed work in fields where women are generally underrepresented: they make up between 20% and 30% of the workforce in physics, and around 30% in computer science (researchers and engineers)2. Twenty years ago, the field of mechanical engineering had so few women that the technical high school Sandra Bosio attended, as well as the companies where she began her career, lacked the proper facilities to accommodate women in the workshops. Without women’s changing rooms, she had to change ‘in offices or in the restrooms.’ In other cases, some companies were unable to host her for internships at all, since they were not equipped with changing rooms. Today, this lack of infrastructure has been somewhat addressed. Sandra Bosio explains that ‘building regulations have changed,’ requiring new companies to provide separate changing rooms for men and women.”

Gender equality is still a long time coming

Although some standards have improved, Sandra Bosio explains that ‘in mechanical manufacturing, nothing has really changed.’ Since joining CNRS, she has only ever hosted ‘two or three female interns’ and remains the only woman in her department. This is a familiar situation for her, as she was ‘the only girl in the class’ throughout her six years of studies and also during her internships.

The experience was different for Valentina Parigi, who was surrounded by nearly as many women as men during her undergraduate studies in Italy in the early 2000s. Twenty years later, Clémence Chevignard has never been the only woman in her lab, class, or university. Yet the numbers were still far from equal.

Moreover, as students progress through their programs, the gap widens, and ‘there are increasingly more men than women,’ Valentina Parigi notes. She often finds herself ‘the only girl in the room,’ a situation that becomes even more common as women advance in their careers. She adds, ‘You see this in all fields: as responsibilities increase, the number of women decreases.’ And she concludes, ‘you can see the glass ceiling.’”

Difficult situations at times

These three women have often faced situations where their credibility was questioned simply because of their gender. For Sandra Bosio, this sometimes meant companies initially refusing to take interns, only to hire her male colleagues shortly afterward. Clémence Chevignard has encountered colleagues who were ‘a bit condescending,’ though she could never be truly certain whether this was due to her gender or her level of experience. Similarly, Valentina Parigi recalls being praised at a conference, along with three other female physicists, ‘because, even though we were women, we managed to give our presentations well.’

Confronted with the persistent challenges women face in physics, a group of quantum physics professors—mostly based in Europe, but also around the world—founded the association Women 4 Quantum, which Valentina Parigi is part of. The organization recognizes that existing initiatives to ‘improve gender balance in the field’ have largely fallen short. Women 4 Quantum aims to drive meaningful change, particularly through redistributing power within the discipline. Their manifesto offers further insight into their vision and goals.

Role models

A concept that has its limitations…

One way to encourage more women to pursue careers in research or engineering is to highlight role models—that is, examples of women working in these fields. For Valentina Parigi, this is not a simple matter. By showcasing people ‘who are the best in the world, who are winners,’ there is a risk of overlooking the fact that ‘research is also done by everyone else.’ Clémence Chevignard echoes this point, warning against the invisibilization of women who are ‘less known, less in the spotlight, but whose work is just as important.’ She adds that the scientists often held up as examples ‘did not live […] within the social context and society we live in today,’ making it difficult to relate to figures from another century.

To make role models truly effective, it is crucial ‘to have contemporary examples’ that can ‘help younger generations identify with these people.’ For Sandra Bosio, these examples do not necessarily need to be famous; even lesser-known figures can play a key role in inspiring women to take the next step in their careers.

… but still essential

On the other hand, role models can also be found in fiction—that is, through representation. This was the case for Clémence Chevignard, who was inspired by a female character in Christopher Nolan’s 2014 film Interstellar. The character, Murphy Cooper, was played by Mackenzie Foy as a child, Jessica Chastain as an adult, and Ellen Burstyn in old age. Originally planning to pursue a litterature-focused high school track, Chevignard ‘changed her mind two weeks before the start of the school year’ and switched to a scientific track after watching the film.

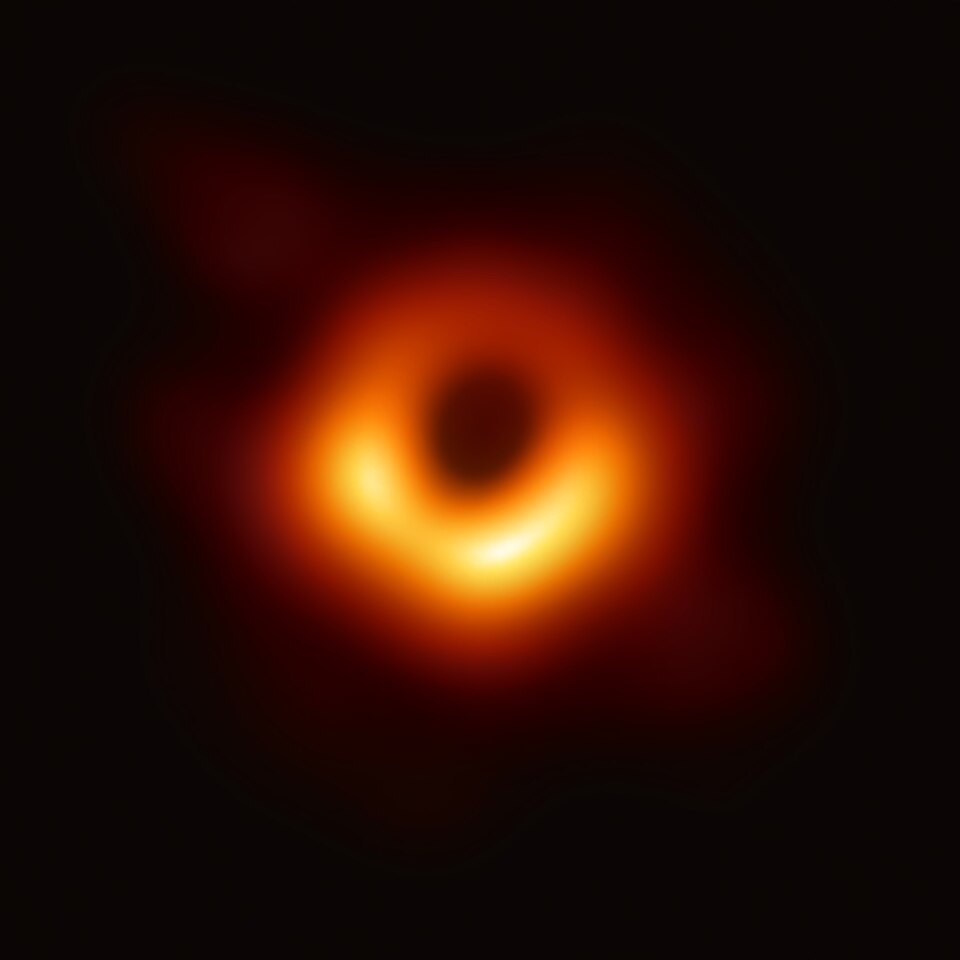

Later, while she was in preparatory school, an American research team succeeded in producing the first-ever image of a black hole using data from the Event Horizon Telescope. What struck her at the time was that the person presenting the results at every conference was a woman: Katie Bouman3. Up until then, Chevignard doesn’t recall ever seeing a female scientist so prominently in the spotlight. It made her realize that it is indeed possible to ‘have a career at that level, in that field, as a woman.

Inspiring new generations to pursue careers in science and engineering

Why choose computer science, physics or engineering?

As a child, Clémence Chevignard dreamed of becoming an inventor, ‘creating machines in [her] large laboratory, Leonardo da Vinci style.’ She saw two possible career paths: engineer or researcher. She chose the latter and gravitated toward mathematics, since working ‘on math problems gives [her] the same thrill as solving puzzles or playing escape games.’ Viewing ‘cryptography research as math in disguise,’ she ultimately built her career in computer science

Valentina Parigi, on the other hand, began her journey driven by ‘philosophical questions.’ She was fascinated by the big questions of life and quickly turned to the scientific method, embracing both theoretical and experimental approaches. As a professor, she is able to combine these two aspects while also ‘engaging with students’ to ‘reexplain the realities.’ In her words, ‘teaching feeds research, and research feeds teaching.’

Sandra Bosio entered the field of micromechanics almost by chance, due to ‘poor guidance from [her] middle school career counselor.’ Yet what began as an accident became a true passion, and she eventually specialized in microtechnology.

Initiatives to promote these fields

To showcase different research careers like her own, Sandra Bosio’s laboratory regularly welcomes middle and high school classes. Students spend half-days at the lab, touring experimental rooms, technical and support services, and attending mini-lectures. For Bosio, this allows young people to ‘truly see the research environment and attract […] future physics master’s students’ or students interested in the field. Valentina Parigi emphasizes this point: ‘What’s important is that students actually come on-site’ to see what doing research really means in practice. She also highlights the value of arts-and-science initiatives, which help connect people who might otherwise be far from science.

Events such as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology 20254 or the CNRS thematic years5 can also help raise awareness of scientific disciplines. These initiatives put important technologies and techniques in the spotlight—technologies that will shape the world of tomorrow. They also create opportunities to ‘generate activities that go beyond what existing labs do,’ for instance through project certifications, explains Parigi. The three women interviewed also emphasize the importance of the annual Science Festival, held every fall, in which many laboratories actively participate.

Changing the narrative

Beyond specific initiatives aimed at encouraging young people—and especially young girls—to pursue research, it is also crucial to change the narrative around what is possible. For instance, when Clémence Chevignard was in high school, some of her teachers advised her against enrolling in preparatory classes, even though she was at the top of her class. The reasons given to her and the other girls were varied, often unfounded, and sometimes arbitrary: they supposedly had no chance, would struggle under stress and pressure, or weren’t competitive enough. Chevignard recalls that this type of messaging had a significant impact on some of her classmates’ career choices.

As Valentina Parigi explains, ‘girls are expected to never make mistakes […] while boys can take all the risks they want.’ That is why she often encourages her students to experiment and ‘not be afraid to change direction later.’ The key is to keep an open mind and show girls ‘that they don’t have to be perfect.’ Chevignard fully agrees: ‘You have to try at least to see what it’s like.’ She also points out that in pursuing a scientific career, ‘the desire to be first just to be first isn’t necessarily the best motivation.’ Supporting students means exposing them to the realities of certain professions—such as the heavy weights Sandra Bosio has to carry in her day-to-day job—but without creating unnecessary barriers.

What’s next ?

In addition to her research and teaching activities, Valentina Parigi is also involved in outreach projects. She intends to continue in this direction, but she is keen to maintain her work in fundamental research. As she puts it, ‘without fundamental research, there will never be applied research. We must continue to support it in all its dimensions.’ Sandra Bosio, who depends on the projects of researchers in her lab, can only agree. The prospect of new challenges and even ‘quirky’ projects is what motivates her work every day. For Clémence Chevignard, ‘the next step is finding a postdoc, followed by a permanent position,’ ideally within her field and in the French public sector.

The PEPR Quantum program wishes them all the very best!

- Work carried out in collaboration with André Schrottenloher and Pierre-Alain Fouque ↩︎

- Resources on gender equality in research in France:

– état de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation en France n°18

– Evolution de la place des femmes en physique

– Rapport social unique CNRS 2024 ↩︎ - Katie Bouman is an American computer scientist and academic. A faculty member at the California Institute of Technology, she specializes in image processing. In 2016, she led the development at MIT of an algorithm that reconstructed the first image of a black hole. ↩︎

- Proclaimed by the United Nations. ↩︎

- Recent thematic years:

– 2025–2026: Year of Engineering, organized by CNRS and the Academy of Technologies

– 2024–2025: Year of Geosciences, organized by CNRS, the Geological Society of France, the National Museum of Natural History (MNHN), and the French Geological Survey (BRGM)

– 2023–2024: Year of Physics, organized by CEA, CNRS, France Universités, and the French Physical Society ↩︎

Written by Lauren Puma

Latest news

No news

More news Interview